|

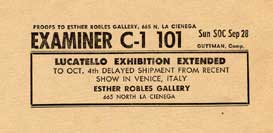

During a one–man show at Bevilacqua Americans arrive: a gallery

in Los Angeles signs a contract with him. For a brief period it

seems as if commercial success pours down on him: they organise

exhibitions, they sell his paintings at high prices to big people

in legendary California. Then suddenly silence. Apparently the rumour

of his communism has reached them, right in the middle of Macarthyism.

And he lost even about forty of his very best paintings.

With that little economic euphoria he takes a new studio in San

Vio and rents a house in San Pietro in Volta for one summer, in

’57, to take his children to.

But he doesn’t paint the sea. A series of “vegetable gardens

in Portosecco” emerges, lumpy and materic lines of dark vegetables,

under white or yellow skies: the object can only just be glimpsed,

but the precise reference to nature cannot be missed. Nature in

which there is the peasant who is unseen, but who is omnipresent

in the humus of that salty earth. And they are followed by the black

material lands, where the lumps of colour even stick out, with flaming

skies at sunset – but also teapots, these unexpected still–lifes

that cut into matter and, further still, make the mixture of nature

and man credible. But as the sense of his work becomes clearer in

his mind, almost as a natural contrast, his uneasiness and intolerance

to bear the Venetian artistic circles becomes more and more acute.

Extremely gentle in human relationships, tolerant and generous towards

the suffering and weakness of feelings, he becomes bitter and rigorous

when painting is involved, because for him painting means cleaning,

it is the moral of truth as far as this can be contingent. Thus

the enthusiastic Lucatello of the early years becomes chronically

angry. At exhibitions he argues with the organizers who want agreement,

with the critics who in the juries discard authentic effort and

are indulgent towards the anonymous throng of beggars. Lucatello

becomes an embarassment. He is always somebody who has “worked

well” three years before. Or perhaps he is good but “went

his own sweet way”. With him there is no chance of dialogue,

he is a bit mad, an isolated. And he in fact isolate himself. Venice

becomes a hated love. He wants to leave, but not just to have supporters

in other art capitals and cliques: his is the choice of an exile.

|